Ethiopian specialties accompanied by injera flatbread at Café Colucci on Telegraph Avenue in Oakland. Photo: Anna Mindess

At Café Colucci on Telegraph Avenue, when you dip your injera into pungent, deftly seasoned creamy lentils, collard greens or chopped beef, you are dipping into thousands of years of Ethiopian culinary history.

“Sheltered in isolation, Ethiopian culinary art flourished autonomously for centuries,” writes restaurant owner Fetlework Tefferi in her book Ethiopian Pepper and Spice. “Farmer families have entrusted the seeds of their crops as well as ancient cultivation processes from father to son, while family spice blending from mother to daughter for generations on end.”

In order to ensure that the dozens of indigenous spices and herbs used in her beloved Oakland restaurant retain their authentic flavor, Tefferi has been passionately supporting the local farmers and dairywomen of Modjo, Ethiopia since 2009.

Several times a year, Tefferi travels to her native land, where a majority of the population is still farming and much of the land has not yet been exposed to the chemicals that would burn the earth. Her goal: to help local farmers thrive using their traditional agricultural methods by ensuring they receive training in everything from irrigation to recycling.

Tefferi tries to enlist the aid of local agronomists to show farmers how to install drip-irrigation systems so they can grow more crops — instead of just waiting for the rainy season. She also supplies stainless steel pots so that women (the traditional dairy farmers) can still make butter by hand, but more efficiently than with traditional clay pots.

Encouraging them to help her fill the growing demand for authentic Ethiopian spices and other food products not only benefits the farmers, Café Colucci’s diners, and the customers of her online spice store, Brundo, it completes a cultural circle that connects Tefferi to her homeland.

When she was still a teenager, Tefferi’s parents decided it would be best to send her to the U.S. to live, considering the situation in Ethiopia at the time. Her mother, who stayed in Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, gave Tefferi a precious package to begin her new life in Michigan: five plastic bags sealed with wax, containing the five most important spice blends that bestow on Ethiopian food its characteristic intensity and flavor.

Tefferi kept the treasured bundles of spices in the freezer of her new home and sprinkled tiny amounts of them onto the unfamiliar (and “bland”) American dishes she was served. Sparingly used, these spice blends lasted for two years, preserving a vital link to her lost homeland and family, and fueling a persistent passion in Tefferi’s life to share the ancient food ways of her native culture.

Over the past 20 years, Tefferi’s award-winning restaurant has introduced thousands of diners to intensely flavored dishes such as doro wat, azifa and buticha, served traditionally atop spongy crêpe-like disks of injera — and always eaten with the hands.

Berbere, a blend of more than twelve spices and the heart of Ethiopian cuisine, takes two weeks to make from scratch. Photo: Anna Mindess

It is hard to overstate the importance of spice blends in Ethiopian dishes. Far from adding a sprinkle of flavor at the end of cooking, they constitute the deep soul of the cuisine, and their creation is considered an art.

Berbere, for example, a crimson blend of more than a dozen spices (each family would have their own recipe) takes at least two weeks to prepare. After the peppers are washed, deveined, trimmed and seeded, they are sun-dried. They are then crushed, sifted, and blended with sacred basil, rue, ginger, garlic and shallots. Honey wine is added to make a thick paste, which is sealed in an airtight container for several days. The paste is again sun-dried and other lightly toasted spices (such as fenugreek, black cumin and cardamom) are added. Finally, the mixture is lightly roasted on a clay griddle and, after cooling, milled into a fine powder.

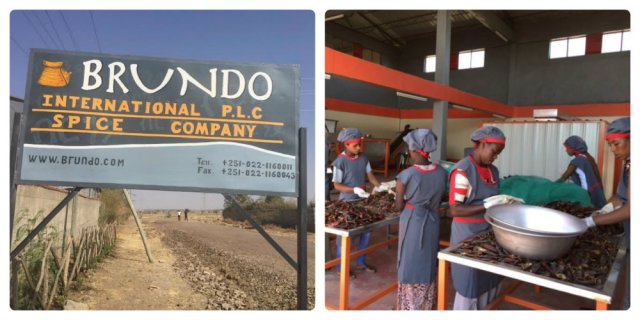

Sixty-five kilometers from Addis Ababa, Tefferi recently built a spice-processing facility, in Modjo, a city that boasts warm breezes, beautiful flowers and rich soil. There, she employs local women to pick, dry and blend the traditional herbs and spices she then imports to sell or use in her restaurant.

“It is thanks to Café Colucci’s customers that we are able to support our work in Ethiopia,” she acknowledges gratefully.

Tefferi speaks passionately about her dream and mission: to preserve and share traditional ingredients and cooking methods from her 3,000-year old Ethiopian culinary heritage, especially the variety of spice blends that are essential to preparing meat and vegetable dishes. On her trips to Ethiopia, Tefferi sees these traditions slipping away as younger Ethiopians turn to fast food.

“We have to help the traditional cuisine live, or it will die, killed by a common palate – burgers,” she said.

Ethiopian souff (safflower seeds): used in salads, mustard, dips and digestive drinks. Photo: Anna Mindess

A quiet manner belies Tefferi’s many accomplishments and steely determination. Besides setting up the spice-processing facility and organizing trainings, she also oversees her restaurant, its sister shop, cooking classes in Oakland, a catering business and the online store. A common thread runs across all these ventures: the need to use Ethiopian-grown spices.

“I’ve tried doing blind-taste tests with turmeric, cumin, and cardamom from Safeway. There is no comparison,” says Tefferi bluntly. ”They taste completely different from those grown on healthy Ethiopian earth.”

Tefferi is careful to balance her relationships with her farmers, buying no more than 40% of any one family’s production and encouraging entrepreneurship.

“It’s a win-win situation. We help farmers by introducing new technology so that they can deliver more good food both in Ethiopia and here,” she said.

She hopes her facility will serve as a model for other similar sites around the country.

And for those who are inspired by Tefferi’s initiatives, there are ways to get involved. Tefferi needs volunteer trainers with experience in organic farming, cultivation, packaging, small-farm irrigation or food processing who are willing to travel to Ethiopia.

“Come for six weeks,” she said with a warm smile. “I can provide food and lodging. We would welcome people who can observe and improve our methods to affect change and help the environment.” If interested, contact her at tefferi1@gmail.com

On February 1, 2015 she officially launched Brundo International, the spice processing plant in Mojo, Ethiopia.

Tefferi also offers catering and Ethiopian cooking classes in Oakland. For more information, visit the Brundo Ethiopian Spices website.

A version of this article first appeared on 1/21/15 on Berkeleyside .com

A version of this article first appeared on 1/21/15 on Berkeleyside .com

Reblogged this on Blue Nile Cuisine and commented:

“Berbere, for example, a crimson blend of more than a dozen spices (each family would have their own recipe) takes at least two weeks to prepare.” So true. Thanks for this great site.